Introduction

The movement of capital often determines the trajectory a society takes. The ethical values with which capital investments are made can, therefore, influence social and environmental outcomes, sometimes even more profoundly than regulatory interventions. But how do we collectively determine the values that capital represents, universally? The answer has been around for quite some time. In 1798, Thomas Malthus, in his renowned work An Essay on the Principle of Population, warned of the risks of overpopulation and resource depletion, indirectly raising concerns about the environmental limits of growth and consumption. Malthusian thought, although focused primarily on population growth, made early reflections on how human activities, including industry and agriculture, should be managed to prevent social and ecological harm.

By the 18th century in the US, Methodists began to vouch against investing in sectors they considered sinful, such as gambling. The Quakers also advocated that investments should reflect moral values and that capital should be used to promote the greater good of society. Demands for responsible investing continued to increase throughout the 20th century. From protests against funding defence contractors to the global response following the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, the concept of ethical investing laid the foundation for what we now know as Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investing, which has become an integral part of mainstream business practises.

By 2006, the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UN PRI) were established to encourage the incorporation of ESG factors into investment decision-making processes. Over the past 18 years, the initiative gained significant momentum, driven by rising awareness about sustainability and responsible investing. With this growing consciousness, the evolution of ESG was witnessed across industries and nations. By March 31st, 2024, the total number of UN PRI signatories had reached 5,345, with Assets Under Management (AUM) amounting to $128.4 trillion.

ESG is a framework that evaluates how well a company addresses issues such as climate change, human rights, and corporate transparency. Even though the principles that ESG embodies have been in place for some time, the evolution of ESG has demonstrated its growing importance, with global ESG assets surpassing $30 trillion in 2022 and projected to exceed $40 trillion by 2030—representing over 25% of the estimated $140 trillion in AUM, according to Bloomberg Intelligence (BI). This shift highlights the increasing demand from investors, regulators, and consumers for companies to align their operations with broader societal goals, such as addressing climate change and fostering ethical labour practises.

In this blog, we’ll explore the evolution of ESG practises in the gold industry, focusing especially on gold mining. Gold mining—particularly informal operations that operate outside strict regulatory oversight—has often been linked to environmental degradation, human rights abuses, political instability, and violent conflicts. Moreover, because gold is extremely valuable and easy to transport, it has become an attractive means for money laundering and other illegal activities. We’ll delve into each aspect of the evolution of ESG-to see how they’ve changed over time within the gold industry.

Environmental Sustainability in the Gold Industry

Environmental concerns in the gold industry have often been associated with deforestation, soil erosion, water pollution, and the use of hazardous chemicals such as cyanide and mercury in the gold mining process. These environmental impacts not only harm ecosystems but also pose significant health risks to local communities. The transformation of environmental practises in the evolution of ESG in the gold industry can be traced back to the 1970s, with the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the US, along with the implementation of the Clean Air Act (1970) and the Clean Water Act (1972). These laws targeted to regulate emissions and effluents from industries, making gold mining companies adopt cleaner technologies and better waste management practises to reduce their environmental footprint.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, the global community began to recognise the need for sustainable development, particularly following the publication of the Brundtland Report (1987), which stated that critical environmental problems resulted from poverty in the South and unsustainable patterns of production and consumption in the North. The report also brought the idea of biodiversity loss into the centre of discourse related to environmental sustainability. Chapter 6 of the Brundtland Report, “Species and Ecosystems: Resources for Development,” highlighted the urgent need to protect disappearing species and ecosystems. This was especially relevant for gold mining, where deforestation and illegal operations, like in the Amazon, severely threaten biodiversity. Responding to these challenges, the gold industry began adopting Biodiversity Action Plans supported by good practise guidance from the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM).

Brundtland Report profoundly influenced how industries, including the gold industry, approached their environmental responsibilities. By the 2000s, voluntary standards such as the International Cyanide Management Code were introduced to regulate the use of cyanide in gold extraction. Later, global agreements such as the Minamata Convention on Mercury (2013) were established to further reduce environmental harm, specifically targeting the use of mercury in artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM).

With the Millennium Development Goals running from 2000 to 2015, followed by the adoption of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 193 countries at the United Nations Headquarters in New York between September 25th and 27th, 2015, a new and stronger commitment to a sustainable future for all was ushered in. This shift had a profound influence on the gold industry, particularly through initiatives such as the World Gold Council’s Responsible Gold Mining Principles (2019). These principles have played an important role in the evolution of ESG in the gold industry. The principles emphasise reducing the use of hazardous chemicals, managing water resources responsibly, and rehabilitating mining sites post-extraction with the goal of ensuring that mining companies can “provide confidence” that their gold has been produced responsibly. This was also an important step in protecting biodiversity, as it encouraged companies to restore natural habitats and protect the ecosystems that their operations might put at risk.

Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) and materiality assessments have also become important tools to assess the environmental impacts of the gold industry at every stage of the process—from extraction to processing and beyond. By evaluating the entire lifecycle of gold production, companies can identify areas where they can reduce energy consumption, water wastage, limit emissions and effluent discharge, and manage waste more effectively.

Follow AKW Consultants on WhatsApp Channels for the latest updates.

Social Responsibility in the Gold Industry

The social aspects of ESG in the gold industry have historically been under the radar, with issues such as poor working conditions, child labour, and the displacement of indigenous communities, especially being associated ASGM. The artisanal and small-scale gold mining sector, according to the World Gold Council, produces about 20% of the world’s newly mined gold and supports the livelihoods of around 15 to 20 million people.

The evolution of ESG through social transformation began in the 1980s and 1990s, with global organisations such as the International Labour Organization (ILO) advocating for better labour conditions and the elimination of child labour. The ILO’s Conventions on Minimum Age (No. 138) and Worst Forms of Child Labour (No. 182), ratified by many countries during this period, were critical in pushing the formal gold industry toward more ethical practises. However, ASGM, due to its informal nature and lack of regulatory oversight, often remained outside the reach of international labour standards.

The focus on human rights expanded significantly in the 2000s with the introduction of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011). These principles emphasised the responsibility of businesses, including gold mining companies, to conduct human rights due diligence and ensure their operations did not contribute to abuses such as forced labour or child labour. Companies are now expected to take clear steps to address human rights risks in their operations. These steps include creating strong anti-harassment policies, providing safe reporting channels, and offering regular training on issues such as sexual harassment, forced labour, and discrimination based on race, gender, or ethnicity. The Responsible Gold Mining Principles (RGMPs) emphasise the need to protect workers’ rights, promote diversity, and ensure fair treatment in all aspects of employment.

Health and safety regulations, such as Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) standards, also play an important role in enhancing social responsibility of the gold industry. These require companies to provide personal protective equipment (PPE), conduct regular health screenings, and organise comprehensive safety training programmes. Companies also need to monitor and report workplace incidents, following guidelines such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). This focus on both health and safety and worker rights marks a significant step in the evolution of ESG practises within the gold industry.

In the same UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights was introduced, the OECD released its Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (CAHRAs). With this guidance, companies sourcing, transporting, or processing gold from such regions were further obligated to enhance supply chain transparency and mitigate risks by following its recommended five-step framework.

Introduction of certifications such as the Fairtrade Gold Standard and Fairmined Standard were also important measures in the evolution of ESG in the gold industry and ensured that workers in the gold industry received fair wages and worked under safer conditions. These certifications also recommend that local communities should directly benefit from the resources extracted from their land. Additionally, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007), which introduced the principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), became an essential framework for gold companies operating in areas where indigenous communities live. However, as mentioned earlier, due to the very nature of ASGM operations, achieving satisfactory compliance with the standards has been difficult. It would require international collaboration toward the formalisation of the sector, along with better support for local communities and access to necessary technological resources to substantially improve environmental and social outcomes.

Governance Practises in the Gold Industry

The governance pillar of ESG ensures that companies in the gold industry operate ethically, transparently, and in a way that benefits all stakeholders, from investors to local communities. Over the years, several key governance frameworks have been established, setting specific standards and practises that have shaped the industry’s approach to corporate governance.

One of the most significant governance reforms in the evolution of ESG in the gold industry was the introduction of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) in 2003. EITI requires companies to disclose payments to governments, such as taxes, royalties, and fees, thereby increasing transparency and reducing corruption in countries where natural resource extraction is a significant part of the economy.

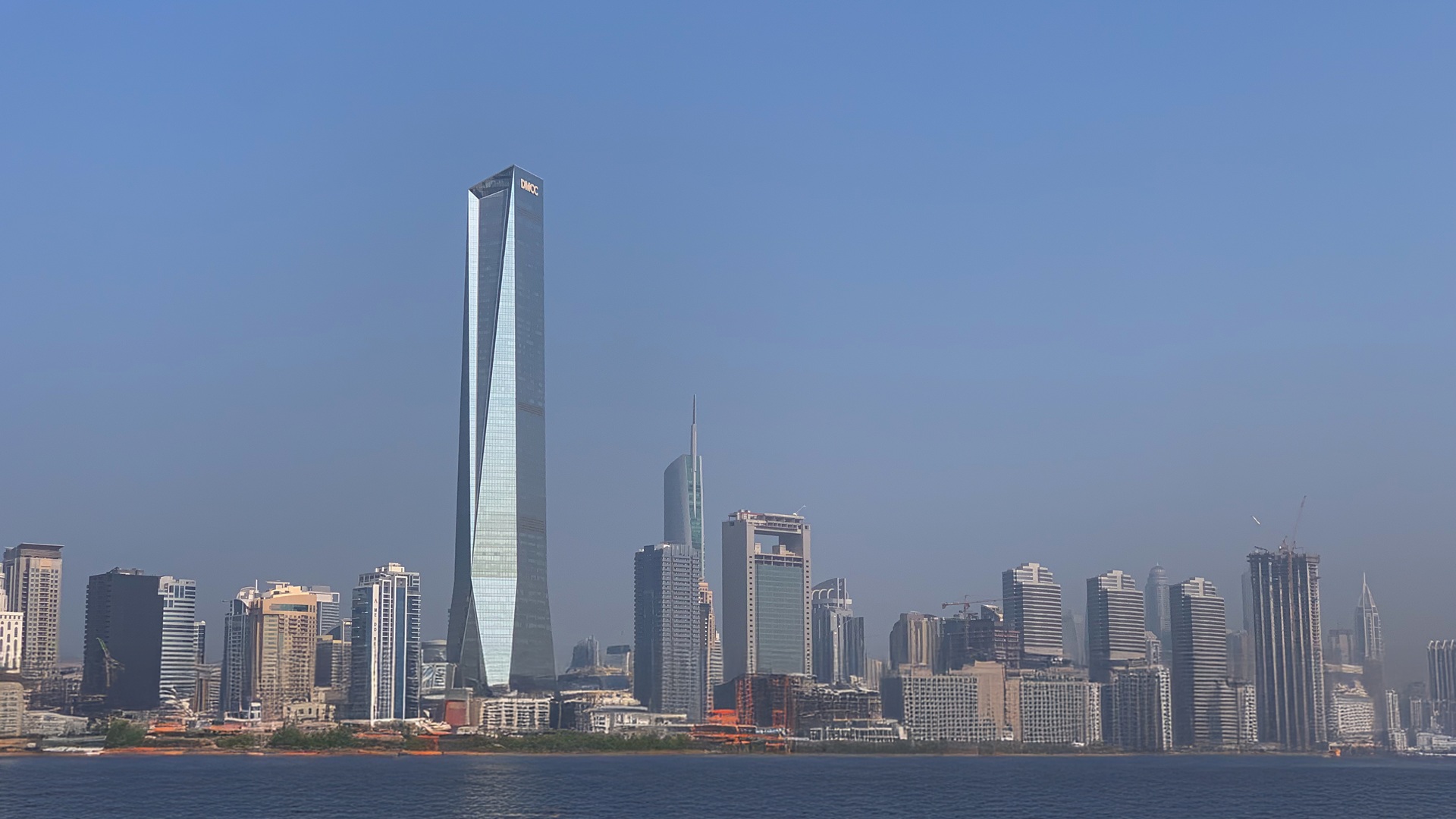

Governance reforms continued into the 2010s with the introduction of London Bullion Market Association’s (LBMA) Responsible Sourcing Program in 2012, which required gold refiners to adopt strong governance systems in line with the OECD framework. In 2022, the UAE Ministry of Economy also introduced Due Diligence Regulations for Responsible Sourcing of Gold based on OECD’s guidelines. These reforms emphasise clear policies, senior management oversight, and independent compliance functions to identify, assess, and mitigate risks. The transparency required for effective governance in the gold industry is also reflected in the UAE Good Delivery (UAEGD) standard, overseen by the Executive Office of the UAE Bullion Market Committee. The UAEGD sets international standards for quality and technical specifications that refineries and gold production facilities in the UAE must meet. By adhering to these standards, UAE gold refineries not only ensure compliance and transparency but also strengthen their global competitiveness and access to international markets, while enhancing governance across the gold industry.

Frameworks such as the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB), Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the United Nations Global Compact have become important tools for investors to assess how well companies manage governance risks and are extremely important in the evolution of ESG in the gold industry. The GRI Standard requires companies to disclose governance structures, including details on board composition, committees, and the roles of the highest governance bodies. Companies are also encouraged to publish ethical guidelines, sharing codes of conduct and ethics policies that govern company behaviour and decision-making. For effective governance, companies in the gold industry engage with stakeholders, provide regular training, and establish grievance redressal systems to give communities and workers a voice. The evolution of ESG in the gold industry is also marked by the implementation of codes of conduct, anti-bribery policies, and a focus on diversity and inclusion within corporate governance.

Transparency around executive compensation is also used to show how remuneration policies align with company performance and governance goals. Companies are expected to detail stakeholder engagement processes, explaining how stakeholder input is integrated into governance and strategic planning, and to highlight risk management practises for identifying and managing governance risks and opportunities.

Conclusion

The evolution of ESG in the gold industry can be viewed from different perspectives: regulatory, financial, or ethical.

Our actions have consequences, whether we intend them or not. Some of these effects are immediate, while others play out over the long term. Regulations, starting with environmental protections in the 1970s, and later frameworks such as the International Cyanide Management Code and the OECD’s guidance, have aimed to address the industry’s environmental, social, and governance issues. But thinking of ESG as just a way to tick regulatory boxes misses the bigger picture, as the success of a company today isn’t just determined by profits—but by how it operates and interacts with the world. And therefore, investors, regulators, and customers have all been demanding more sustainable and ethical practises from businesses. Customers want to know the products they buy are responsibly sourced, and investors see companies that embrace ESG as more responsible, resilient, and ready for the future. In fact, as reported in The Luxembourg Chronicle, a study found that 77% of institutional investors plan to stop investing in non-ESG products altogether.

The gold industry, with its unique challenges, is a perfect example that shows the evolution of ESG and our perceptions of it. From addressing environmental damage to improving working conditions and supply chain transparency, embedding ESG practises goes beyond regulatory compliance—it’s about doing business in a way that positively impacts both people and the planet. As the demand for transparency and accountability grows, companies that commit to ESG will be the ones shaping the future of the gold industry.

At AKW Consultants, we assist companies in driving sustainable growth by improving both financial and non-financial performance. We help businesses develop and implement sustainability strategies, conduct materiality assessments, engage with stakeholders, and review governance practises. We are one of the UAE Good Delivery Reviewers, recognised widely for our integrity and expertise in the Gold and Precious Metals sector. Whether it’s managing sustainability risks or improving overall governance, we help position your company for long-term success in a market moving steadily towards responsible business practises.